Emily Keefer is a participant with the Alamosa, Colorado, Mennonite Voluntary Service (MVS) unit. This post originally appeared on her blog, and has been edited here for length. Click here to read her blog in full. Mennonite Voluntary Service is a one-year service experience of Mennonite Mission Network for individuals age 20+, with the opportunity for a placement extension for an additional one to two years. Applications for the 2026-27 service term are now open! Click here for more information and to apply.

I sit on the floor of my bedroom, fingers prying open plastic packaging. Inside is dried mango brought back from Thailand, by way of North Carolina, now gracing the town of Alamosa. For all its criticisms, sometimes I am unabashedly grateful for globalization. The fruit is a deliciously pale yellow, not the small curled brown pieces sold by Trader Joe’s. Sugar dusts the outside, the edges are almost translucent, melting in your mouth.

Whenever I eat dried mango, I think about the book Inside Out and Back Again, the story of a young Vietnamese refugee told through poetry by Thanhha Lai. In the story, Hà’s favorite fruit is papaya, and she compares the fruit to her own body and her home in Vietnam. When her family is relocated to Alabama she grieves the loss of her papaya tree. Later, a friend gifts her dried papaya, knowing that it’s her favorite fruit. It tastes of disappointment, making her cry because it’s so much worse than the fresh fruit she grew up with. Quietly, her mom rescues the package from the trash, soaks the pieces in water, washes off the sugar, and reheats it in the microwave, trying to return it to a more familiar texture.

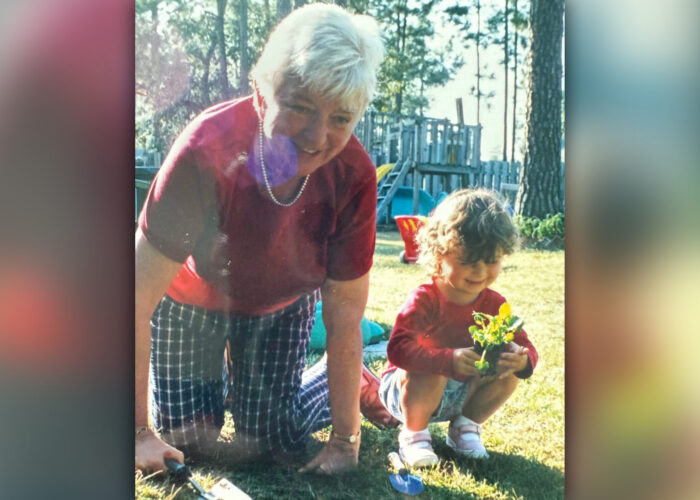

In college, a friend heard me share about how I missed the mangoes I had grown up with in Thailand. I described the Asian mangoes I missed from home, how the skin was thin and yellow, different from the swollen red mangoes from Mexico that were more available in the states. One day she arrived at work with a plastic bag full of yellow mangoes that she had gone to find at an Asian grocery store. I almost cried, it felt like one of the kindest things anyone had done for me.

Thankfully, I love dried mango just as much as fresh mango. I share one package with my coworkers, and I hide the other in my room, carefully rationing the pieces out on sadder days. A little piece of golden, sugary joy. A little piece of home. A little piece of myself.

Just before my sophomore year of high school my family moved from Thailand, where I had spent ten years of my life, to North Carolina, a place I had never been. In Thailand I had been an insider. Ten years of experience in an expat community where people frequently cycled in and out gave me and my family a certain level of seniority and power. In North Carolina I was suddenly the new kid. It was a total loss of power and identity. I remember feeling resentful that no one knew who I used to be. I was not at the center anymore; I was an outsider.

I cannot romanticize this experience. It was the worst year of my life. I read Inside Out and Back Again, suddenly identifying with elements of Hà’s refugee experience (which to be clear is much more extreme and I cannot claim to understand). Falling off a pedestal is painful, and you find yourself amongst the people you used to look down on or pity. You become one of the people you used to dread inviting. You become desperate for such an invitation.

In college I read a profound piece by Willie James Jennings where he insists that White Americans must remember that we are the Gentile outsiders, graciously grafted into God’s story. This is a truth that rubs up against our false mythology of the American founding and whiteness, and our convenient comparisons of our nation to ancient Israel. We are not the center, choosing whether to include others or not. It is only by remembering our position as outsiders who have been brought into the family of God that we can then humbly include others. If we forget our own inclusion, we become arrogant and prone to fantasies that we are at the top of God’s ‘hierarchy’ and the arbiters of ‘true’ Christianity.

This reminder that we were once the stranger echoes throughout Scripture as well. Over and over in the Old Testament, God commands the ancient Israelites that “Do not mistreat or oppress a foreigner, for you were foreigners in Egypt.”1 It is their past existence as strangers and foreigners that should lead God’s people to be merciful and welcoming to strangers and foreigners. It is a commandment that insists on empathy towards the outsider.

In the New Testament this command is expanded. Paul commands the church to remember. “Therefore, remember that formerly you who are Gentiles by birth…remember that at that time you were separate from Christ, excluded from citizenship in Israel and foreigners to the covenants of the promise, without hope and without God in the world. But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far away have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For he himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility”2.

We remember our status as outsiders, as those far away, as those excluded and without hope. Why? Because when we remember our status as outsiders, we see ourselves as connected to those the world tells us we have no relation to. When I experienced being an outsider my sophomore year, I suddenly saw myself as connected to the girls on my soccer team who were literally refugees. I saw myself as connected to women going through re-entry from the prison system, experiencing culture shock to communities they had been isolated from for years.

By remembering our own exodus, our salvation from alienation back into belonging, we are able to see ourselves as siblings to everyone. The dividing walls of hostility have been removed. Paradoxically, remembering that we are outsiders allows us to belong to everyone.3

I’ve been reading Bonhoeffer’s Life Together, a manual for Christian living written while he was incarcerated in Nazi Germany. I’ve been struck by his opening reflections on loneliness and feeling like an outsider. He writes that “God’s people remain scattered, held together solely in Jesus Christ, having become one in the fact that, dispersed among unbelievers, they remember him in far countries.”4 These words have a particular potency coming from Bonhoeffer as he is imprisoned, isolated from loved ones because of his actions to undermine the Nazi regime. The hope of return after exile is not restricted to the ancient Israelites, it is a longing felt by all whose obedience to Jesus has led them into seasons or places of loneliness.

My time with Bonhoeffer’s text, so informed by his own life, have also caused me to reflect on one of my favorite movies, “A Hidden Life” directed by Terrence Malick. The film tells the true story of Fani and Franz, Austrian farmers struggling with Franz’ Christian conviction that he cannot swear an oath of loyalty to Hitler and join the Nazi army.

A character remarks that the church has done a great job of creating admirers of Christ and failed at developing followers. It’s a line that cuts through to me today. Am I really willing to suffer the consequences of following Christ? When my government is contributing to genocide am I willing to suffer material consequences for the sake of the strangers being massacred? When my government is abducting and imprisoning Christian siblings and neighbors because of a lack of documentation, what will I do? Am I willing to go to jail? Am I willing to give up a ‘promising future5? Am I willing to lose my own life for someone else?

The witness of Franz is that you become truly free when you are willing to give up everything, even your own dear life for the sake of faithfulness to God. It is another paradox of Christianity, that by giving up your life you gain it. When you fall off the pedestal of power, you find belonging. When you love your neighbor, you become a neighbor.

At this risk of this becoming overly heavy, I want to return to the mangoes. There is a time for extreme sacrifice on behalf of others. There is also a time for loving the stranger in simple ways. In fact, it may be that by being faithful in little6 that we eventually become courageous enough for the big moments. Maybe I can’t give up everything right now. I can still look for the outsiders in my own life. The people with their backs against the wall7, the poor, the poor in spirit. I can recognize in these people “the Christ who is present in the body” and meet them as “one meets the Lord.”8 I can give and receive fresh mango and papaya.

- Exodus 22:21, NIV ↩︎

- Ephesians 2:11-14, NIV ↩︎

- Read Andrew DeCort’s new book, Reviving the Golden Rule to learn a more comprehensive overview of the golden rule: Christ’s call to love our neighbors, our enemies, and the ‘other’. ↩︎

- Bonhoeffer, Dietrich, and John W. Doberstein. Life Together: The Classic Exploration of Christian Community. HarperOne, 1954, 18.

Bonhoeffer is quoting Zechariah 10, “Though I scatter them among the peoples, yet in distant lands they will remember me. They and their children will survive, and they will return. I will bring them back from Egypt.” ↩︎ - “when you motor away… when you free yourself from the chance of a lifetime… you can be anyone they told you to.” From the song, Motor Away by Guided By Voices. ↩︎

- Luke 16:10, NIV ↩︎

- Howard Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited ↩︎

- Bonhoeffer, Dietrich, and John W. Doberstein. Life Together: The Classic Exploration of Christian Community. HarperOne, 1954,18. ↩︎