The Bible contains more than 100 Scriptures emphasizing church unity. So why do those who believe in Jesus tend to struggle with being unified?

Recently, I was on a learning tour in Accra, Ghana, with a group of African American Mennonite leaders invited to connect and build unity with fellow African church leaders. Our group had representatives from Mennonite Church USA, LMC and Mosaic Mennonite Conference. We were hosted by Dr. Thomas Oduru, president of Good News Theological Seminary — a Mennonite Mission Network partner — and we worshipped at different congregations. I felt right at home worshipping at Trinity Chapel, the Ghana Mennonite Church headquarters. Pastor Francis Dzivor, president of the Ghana Mennonite Church, delivered a powerful and thought-provoking message about Jesus’ Last Supper.

Ghana is a majority-Christian country, primarily because of the influence of Western missionaries in past centuries. Beginning in the 1920s, locally led congregations, including successful African-Initiated Churches emerged and have continued growing today. As we drove south from Accra to Cape Coast, we saw several churches of different denominations dot the landscape. This was encouraging, but I wondered if nonbelievers would see disunity or different biblical interpretations causing church splits.

But is disunity always negative? The Anabaptist movement resulted from a necessary church split, right?

Echoes in a dungeon

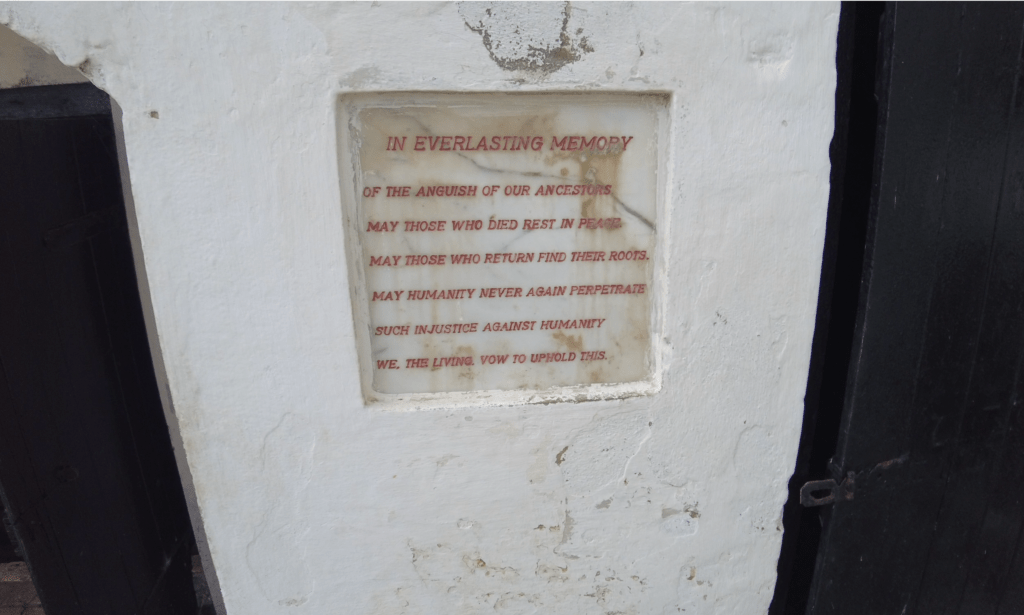

IN EVERLASTING MEMORY OF THE ANGUISH OF OUR ANCESTORS

MAY THOSE WHO DIED REST IN PEACE

MAY THOSE WHO RETURN FIND THEIR ROOTS.

MAY HUMANITY NEVER AGAIN PERPETRATE

SUCH INJUSTICE AGAINST HUMANITY

WE, THE LIVING, VOW TO UPHOLD THIS.

Our tour took a sobering turn, as we visited Cape Coast Castle, a slave post where our African ancestors were dehumanized and stored in a dungeon before being shipped as cargo to the Americas. The tour guide explained that European Christians intentionally built the castle’s sanctuary atop the dungeon. These churchgoers worshipped in the sanctuary — their heaven — while African men, women and children agonized below — in their hell. Standing in the dungeon, as my ancestors had, I peered above through an open shaft to see the church’s blue wooden front door. Our enslaved ancestors were forced to stand or lay side by side, shackled. The guide said their flesh, sweat, blood, urine and feces had petrified to form the dark stone floor beneath our feet. The Africans who rebelled and fought for freedom were tortured, killed and dumped into the sea.

My emotions triggered reflections about what happened to them — us — on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. I recalled seeing the British “Slave Bible” on exhibit at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., a few years ago. White Christians used their tampered version of the Bible to convert enslaved Africans. Scriptures that might inspire rebellion and freedom were omitted. I thought about the irony of my undergraduate education at Lincoln University of Pennsylvania, the nation’s first degree-granting Black college. The university was founded as Ashmun Institute by abolitionists — a Presbyterian White minister, his Quaker wife, and the local free Black community — in 1854, when slavery was still legal! Members of The American Colonization Society established the university to train Black men to be missionaries to Liberia, as part of the “Back to Africa Movement.” They believed that educated free Black people threatened their White social order and therefore Black people had no safe future in America as equals. These abolitionists set their sights on Christianizing Africa. The university’s motto, then, was John 8:36, “If the son shall make you free, then ye shall be free indeed.”

A radical vision

Lincoln University was inspired by James Ralton Amos, a free Black man and trustee at the Hosanna Meeting House, an African Union Methodist Protestant Church in the free Black community of Hinsonville, Pennsylvania. A man of deep faith, Amos, known by his middle name — Ralston — rejected the notion that Black people were less than human. He knew he was made in the image of God, possessing the intellect for higher education, equal to any man. Amos applied to Princeton University’s Theological Seminary, where the White southern elite sent their sons to become leaders. It was a bold statement made by Amos, a full decade before the start of the American Civil War. Princeton, of course, denied Amos because he was Black.

This prompted Amos’s mentor, local Presbyterian pastor the Rev. John Miller Dickey, and his wife, Sarah Cresson — a Quaker — to lead Princeton’s “Radical Republicans” to help fund and establish Lincoln University. Amos also raised funds and the Hinsonville community provided land. Black and White believers unified in doing God’s mission, despite their differences. Proof of the good that happens when God’s people unify. Nonetheless, in 1861, southern Presbyterians split from the denomination over slavery and theology and the Civil War.

Ralston Amos and his brother, Thomas Amos, graduated as part of the first class, in 1859, and joined the ranks of Black missionaries to Liberia and other African regions. African men also came to America to study. Black missionaries, like the Amos brothers, helped transform the pain of the transatlantic holocaust into promise. Decades later, a young Christian named Kwame Nkrumah left Ghana for the United States to attend Lincoln University where he bonded, exchanged ideas and strategized with Black American classmates. After earning a theology degree, in 1942, Nkrumah returned to Ghana, leading it to independence from British colonial rule in 1957. He became the country’s first Prime Minister (1957–1960) and then its first President (1960–1966).

The unity in our group of American and African Mennonite leaders embodied the Pan-African vision legacy of early Black missionaries, like the Amos brothers, and leaders like Nkrumah.

- Learn more about Samia Yaba Nkrumah

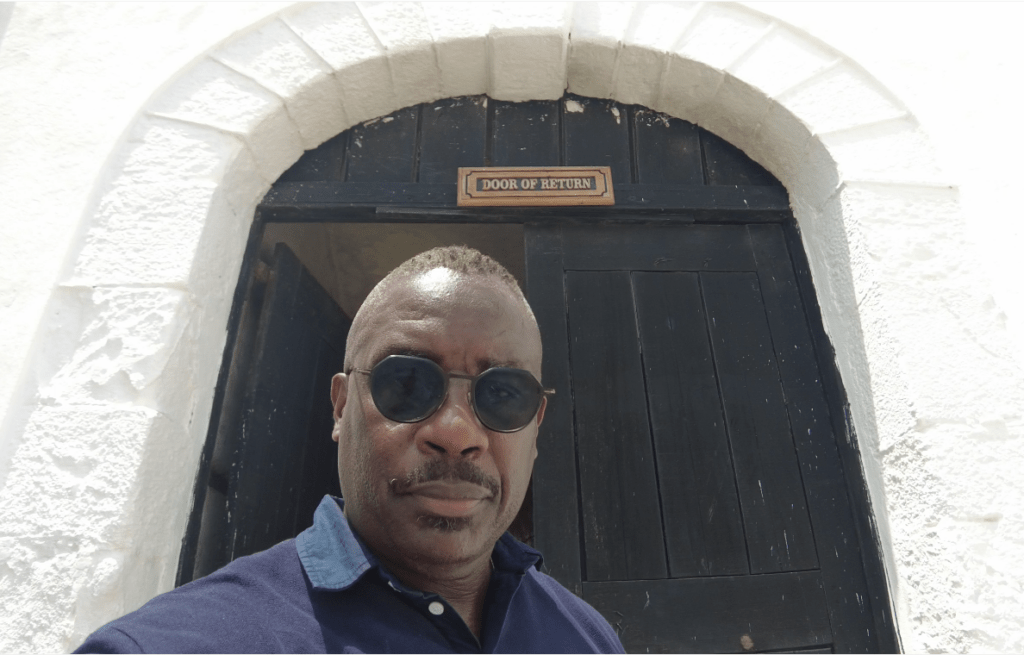

Door of Return

From the dark dungeon, our guide led us toward the infamous Door of No Return. Slowly, we walked through it, as our ancestors had. Our teary eyes squinted from the bright sun and blue sky outside. I paused and gazed at the waves of the Atlantic Ocean. The guide, then, led us back through the opposite side of the door, marked Door of Return. “Akwaaba! Welcome home,” he said. Our ancestors had not sacrificed in vain.

Jesus’ prayer for unity

So, then, why does God emphasize church unity? The High Priestly Prayer in John 17 offers a powerfully clear answer. Knowing that he would soon go to the cross to fulfill his mission, Jesus prayed for his disciples and all future believers.

Jesus prayed his true followers would unite, reflecting the trinity’s unity, so that nonbelievers would be drawn and convinced to follow Jesus, too.

Perhaps we struggle with church unity, because we make it only about us — like looking into a mirror. But the call for unity among believers is more about reflecting Jesus’s love for those who are watching us.

What do they see?

To support our work with Ghana Mennonite Church – donate to the Mennonite Mission Network General Fund.